Teachers: I’ve had a lot of them. Some I recall for their

names, others for their engaging communications, still others for the lack of

impact they made on me. From grade school I recall Miss Weenes whom we second

graders called Miss Weenie, although not in class, and Mrs. Schaffer who read

“Treasure Island” to us, my first novel; there were others whose names escape

me, but I do recall the woman who taught us cursive writing in fifth grade leaving

me with a rather readable hand and the rather effeminate man who taught music

in fourth and fifth grades introducing us to Bizet’s “Carmen.” From junior high

I recall Mr. Moon who at the board always pointed with his middle finger and

who told memorable stories about science, Miss Oliver who taught Latin not only

to me but to my older sisters and to my mother, the effective algebra teacher who

also taught my mom and started geraniums in the windows of her classroom, and

Miss Costello who sent home a mustard plaster recipe when too many students got

colds. From high school I remember Mr. Martin the choir director, Mr. Snodgrass

the band director, Miss Perkins the Latin teacher and drama coach, and Mr. Unruh

the football coach and government teacher. In college, I remember Dr. Van Buren,

President Lown, Mr. Secrest, and Professor Jamie Morgan; in graduate school,

Mrs. Kiesgen and Dr. Lee; in seminary Dr. Duke, Dr. Routt, Dr. Hoehn, and Dr.

Rowell. But that’s only the beginning of the list. I also had music teachers in

piano and voice studios, art teachers at the Oklahoma Art Workshops, leaders of

numerous seminars and workshops at hotels and conference centers, and informal

mentors whose revelations and advice paved the way for a rich life of learning,

work, and enjoyment. Trying to list all my teachers indicates I learned many

things from many different instructors over a long life. I owe a lot to these

people.

names, others for their engaging communications, still others for the lack of

impact they made on me. From grade school I recall Miss Weenes whom we second

graders called Miss Weenie, although not in class, and Mrs. Schaffer who read

“Treasure Island” to us, my first novel; there were others whose names escape

me, but I do recall the woman who taught us cursive writing in fifth grade leaving

me with a rather readable hand and the rather effeminate man who taught music

in fourth and fifth grades introducing us to Bizet’s “Carmen.” From junior high

I recall Mr. Moon who at the board always pointed with his middle finger and

who told memorable stories about science, Miss Oliver who taught Latin not only

to me but to my older sisters and to my mother, the effective algebra teacher who

also taught my mom and started geraniums in the windows of her classroom, and

Miss Costello who sent home a mustard plaster recipe when too many students got

colds. From high school I remember Mr. Martin the choir director, Mr. Snodgrass

the band director, Miss Perkins the Latin teacher and drama coach, and Mr. Unruh

the football coach and government teacher. In college, I remember Dr. Van Buren,

President Lown, Mr. Secrest, and Professor Jamie Morgan; in graduate school,

Mrs. Kiesgen and Dr. Lee; in seminary Dr. Duke, Dr. Routt, Dr. Hoehn, and Dr.

Rowell. But that’s only the beginning of the list. I also had music teachers in

piano and voice studios, art teachers at the Oklahoma Art Workshops, leaders of

numerous seminars and workshops at hotels and conference centers, and informal

mentors whose revelations and advice paved the way for a rich life of learning,

work, and enjoyment. Trying to list all my teachers indicates I learned many

things from many different instructors over a long life. I owe a lot to these

people.

Mother taught us kids to respect our teachers although she

well knew they had feet of clay. She supported them through her tireless work

in the PTA but also challenged them when their behavior overstepped their role

of teacher and nurturer of young people. So when I heard harangues from the

pulpit that some faithless people scandalously thought of Jesus as only a

teacher, I felt unsettled. Mom taught us that being a teacher was one of the

very best occupations anyone could pursue. Of course, those preachers were

defending the orthodox doctrine of the divinity of Christ. I was not concerned with

orthodoxy and thought if Jesus back then or as a spiritual presence could teach

anyone, he could be my teacher as well and earn my deepest respect. Like Mom, I

liked my teachers. Two, though, stand out as the most influential: the first

for inspiration, the second for technique.

well knew they had feet of clay. She supported them through her tireless work

in the PTA but also challenged them when their behavior overstepped their role

of teacher and nurturer of young people. So when I heard harangues from the

pulpit that some faithless people scandalously thought of Jesus as only a

teacher, I felt unsettled. Mom taught us that being a teacher was one of the

very best occupations anyone could pursue. Of course, those preachers were

defending the orthodox doctrine of the divinity of Christ. I was not concerned with

orthodoxy and thought if Jesus back then or as a spiritual presence could teach

anyone, he could be my teacher as well and earn my deepest respect. Like Mom, I

liked my teachers. Two, though, stand out as the most influential: the first

for inspiration, the second for technique.

I knew Dr. James Van Buren by reputation long before I got

to school and took his demanding class, “Survey of Biblical Literature.” After

that there were other classes in biblical studies, philosophy, theology, sociology,

and literature. Studying in a small college, I got to make a rather thorough

study of this professor who was both the hardest one to get good grades from

and the one who opened worlds of knowledge most widely. I can say confidently

that Dr. Van taught me how to run successfully on the liberal edge of

conservatism. By ‘successfully’ I mean not only getting beyond political

hurdles but also doing so while maintaining theological self-respect and

integrity. He taught me to read broadly, to think openly, and to communicate

creatively. For instance, he lectured on Christian humanism, Christian

hedonism, Christian stoicism, and Christian Epicureanism insisting that

Christian thought was not a complete philosophy in itself but a base from which

one examined and utilized perspectives of the ages. He taught humor as an

essential ingredient in the most serious communications and sex as a broadly

celebrative dynamic of life. In Dr. Van’s approach God as the creator and

approver of creation served as the starting point and essential part of a

healthy approach to life, morality, and ethics. He insisted that creative and

playful thinking stands as a necessary component in one’s life and insisted

religion should never become a wooden legal transaction or set of rigid laws.

He taught an appreciation for beauty through arts, literature, science, and everyday

interactions with fancy and plain people. Poetry, storytelling, drama, and

lively insights transformed theology into a process for living. The arts

pointed to dynamic creativity in the name of the Creator.

to school and took his demanding class, “Survey of Biblical Literature.” After

that there were other classes in biblical studies, philosophy, theology, sociology,

and literature. Studying in a small college, I got to make a rather thorough

study of this professor who was both the hardest one to get good grades from

and the one who opened worlds of knowledge most widely. I can say confidently

that Dr. Van taught me how to run successfully on the liberal edge of

conservatism. By ‘successfully’ I mean not only getting beyond political

hurdles but also doing so while maintaining theological self-respect and

integrity. He taught me to read broadly, to think openly, and to communicate

creatively. For instance, he lectured on Christian humanism, Christian

hedonism, Christian stoicism, and Christian Epicureanism insisting that

Christian thought was not a complete philosophy in itself but a base from which

one examined and utilized perspectives of the ages. He taught humor as an

essential ingredient in the most serious communications and sex as a broadly

celebrative dynamic of life. In Dr. Van’s approach God as the creator and

approver of creation served as the starting point and essential part of a

healthy approach to life, morality, and ethics. He insisted that creative and

playful thinking stands as a necessary component in one’s life and insisted

religion should never become a wooden legal transaction or set of rigid laws.

He taught an appreciation for beauty through arts, literature, science, and everyday

interactions with fancy and plain people. Poetry, storytelling, drama, and

lively insights transformed theology into a process for living. The arts

pointed to dynamic creativity in the name of the Creator.

This overweight professor rested a little notebook on his

stomach as if it were a lectern. This enthusiastic professor lectured from the

book of Job on the dances of whales in the ocean, leaping about like one of

them himself. This insightful professor opened the way to Shakespeare, Milton, and

Whitman. This scholarly professor had been granted a DD and then earned a PhD

in English Literature, his dissertation an examination of Old Testament Apocryphal

references in John Milton’s poetry. This superlative teacher supported in me my

love for books and libraries and my proclivity toward creative thinking in

matters of education and religion. I continue to think about Dr. Van Buren’s

advice, knowledge, and approach whenever I try to solve problems or speak from

my own heart.

stomach as if it were a lectern. This enthusiastic professor lectured from the

book of Job on the dances of whales in the ocean, leaping about like one of

them himself. This insightful professor opened the way to Shakespeare, Milton, and

Whitman. This scholarly professor had been granted a DD and then earned a PhD

in English Literature, his dissertation an examination of Old Testament Apocryphal

references in John Milton’s poetry. This superlative teacher supported in me my

love for books and libraries and my proclivity toward creative thinking in

matters of education and religion. I continue to think about Dr. Van Buren’s

advice, knowledge, and approach whenever I try to solve problems or speak from

my own heart.

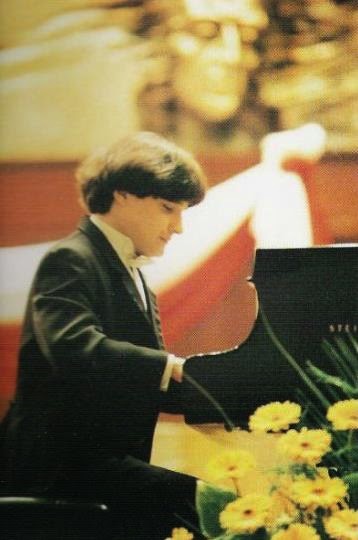

I knew Dr. Karen Bartman years before she was conferred a

doctoral degree in piano pedagogy. She served as the church’s music coordinator

and organist where I worked as associate minister and director of the Chancel

Choir. We made music together for several years before I studied in her piano

studio. I recall this teacher for both her pianistic and pedagogical techniques—carried

out with consistency, musical depth, and always the encouragement to keep

making beautiful music. I’ll never know if I could have learned piano technique

at an earlier age, but I did learn it in my late thirties under her tutelage.

When I approached my 40s crisis (a la Goldberg and Sheehe), I became

“angry with the gods of literature” as my friend Gerald put it and went on a yearlong

book fast. I joined Karen’s studio to learn to play piano, knowing I’d have

about three hours a day to practice, time I would not be reading books. I

remained a student in her studio for two and a half years. Since childhood I had

played—my father said banged—the piano but always with great limitation. Gerald

once said I was quite musical but had no technique. After two years of Karen’s

discipline I played a piece for my dad. He declared, “She’s a miracle worker;

you’re not pounding.” Even Gerald seemed impressed at her work and my response,

and Dr. Bartman said what she appreciated about teaching me—an adult—was that I

always played musically.

doctoral degree in piano pedagogy. She served as the church’s music coordinator

and organist where I worked as associate minister and director of the Chancel

Choir. We made music together for several years before I studied in her piano

studio. I recall this teacher for both her pianistic and pedagogical techniques—carried

out with consistency, musical depth, and always the encouragement to keep

making beautiful music. I’ll never know if I could have learned piano technique

at an earlier age, but I did learn it in my late thirties under her tutelage.

When I approached my 40s crisis (a la Goldberg and Sheehe), I became

“angry with the gods of literature” as my friend Gerald put it and went on a yearlong

book fast. I joined Karen’s studio to learn to play piano, knowing I’d have

about three hours a day to practice, time I would not be reading books. I

remained a student in her studio for two and a half years. Since childhood I had

played—my father said banged—the piano but always with great limitation. Gerald

once said I was quite musical but had no technique. After two years of Karen’s

discipline I played a piece for my dad. He declared, “She’s a miracle worker;

you’re not pounding.” Even Gerald seemed impressed at her work and my response,

and Dr. Bartman said what she appreciated about teaching me—an adult—was that I

always played musically.

This physically fit teacher sat at the keyboard with

perfect posture and insisted I do so as well. This enthusiastic teacher with

beautifully strong hands didn’t just give me scales and arpeggios to strengthen

my hands but showed me how to execute them in ways that engaged listening,

phrasing, and trusting that my hands would know where they were on the

keyboard. This insightful teacher showed me how to ground myself at any point

in a phrase, a measure, or a beat giving life to the composition in

performance. This scholarly teacher helped me know Bach, Mozart, Brahms,

Schubert, Schumann, Chopin, Debussy, Mompou, Shostakovich, and Prokofiev in

ways I had never grasped even after extensive graduate study in musical style

analysis. This superlative teacher inspired me to practice with confidence that

I could play effectively and beautifully. Eventually I quit piano instruction

and returned to books and writing. Still, I continued to practice and put to

use my grasp of her technique when I played. From her I learned the value of

technical proficiency. Her consistent teaching encouraged me to continue to

develop as an artist and to bring artistry to bear in all my work.

perfect posture and insisted I do so as well. This enthusiastic teacher with

beautifully strong hands didn’t just give me scales and arpeggios to strengthen

my hands but showed me how to execute them in ways that engaged listening,

phrasing, and trusting that my hands would know where they were on the

keyboard. This insightful teacher showed me how to ground myself at any point

in a phrase, a measure, or a beat giving life to the composition in

performance. This scholarly teacher helped me know Bach, Mozart, Brahms,

Schubert, Schumann, Chopin, Debussy, Mompou, Shostakovich, and Prokofiev in

ways I had never grasped even after extensive graduate study in musical style

analysis. This superlative teacher inspired me to practice with confidence that

I could play effectively and beautifully. Eventually I quit piano instruction

and returned to books and writing. Still, I continued to practice and put to

use my grasp of her technique when I played. From her I learned the value of

technical proficiency. Her consistent teaching encouraged me to continue to

develop as an artist and to bring artistry to bear in all my work.

In summary, Dr. Van Buren taught me to love life and the

arts, Dr. Bartman encouraged me to find consistent techniques for any creative

work I undertook. My life as a learner continues inspired and enabled by these

two great teachers. There have been plenty more teachers, loads of learning,

and lots of creative outcomes that today I celebrate along with this litany of my

teachers’ names.

arts, Dr. Bartman encouraged me to find consistent techniques for any creative

work I undertook. My life as a learner continues inspired and enabled by these

two great teachers. There have been plenty more teachers, loads of learning,

and lots of creative outcomes that today I celebrate along with this litany of my

teachers’ names.

© 1 Nov 2011

About the Author

Phillip Hoyle

lives in Denver and spends his time writing, painting, and socializing. In

general he keeps busy with groups of writers and artists. Following thirty-two

years in church work and fifteen in a therapeutic massage practice, he now

focuses on creating beauty. He volunteers at The Center leading the SAGE

program “Telling Your Story.”

lives in Denver and spends his time writing, painting, and socializing. In

general he keeps busy with groups of writers and artists. Following thirty-two

years in church work and fifteen in a therapeutic massage practice, he now

focuses on creating beauty. He volunteers at The Center leading the SAGE

program “Telling Your Story.”

He also blogs at artandmorebyphilhoyle.blogspot.com