It is not enough to be busy. So are the ants.

The question is: what are we busy about? –Thoreau

Today’s prompt is the party, not a party. The party to me means a special party, a party to end all parties. We’ve all been to many a parties. But to satisfy today’s prompt–the party–I felt I had to go into the crawlspace of my memories to see if I could find some party I’d been to that was the Mother of All Parties. Luckily, I didn’t have to spend too much time in the crawlspace.

Not only did I find my personal Mother of All Parties without a lot of rummaging around but also I found, in remembering my one and only the party, the baseline from which I’ve taken the measure of the last three decades of my life.

Go back with me for a moment to February 1980. Jimmy Carter’s in the White House. When not trying to figure out how to send this thing called a fax, we’re playing an addictive game called Pac Man. In bookstores, it’s Sophie’s Choice. On Broadway, it’s Evita. In movie theaters, it’s Raging Bull. But join me on the 10th floor of the Coachman over on Downing across from Queen Soopers. It’s a little after 8 and I’m coming home, tired, from somewhere. I walk into my apartment, the one I share with my partner Jim to find the place usually dark–not one light left on. That’s unusual. I know something’s wrong: there’s a kind of creepy aliveness in the dark–like stepping into a lightless grizzly den. But then lights throughout the apartment go on. I’m standing inside the front door looking at a place packed to the sidewalls with people, all looking at me and yelling, “Surprise!”

It’s my 35th birthday and Jim has schemed the Mother of All surprise parties for me. When I say the apartment is packed, I mean it is PACKED. Jim and I work for one of Denver’s now-long-gone Capitol Hill theaters and here in our apartment is the acting company, directors, staff, costumers, carpenters, and crew. Jim’s day-job is with a 17th Street bank; I know Jim’s co-workers and they’re here, too. My day-job is with a medical supply house; Jim knows my co-workers and he’s invited them as well. Add to the mix other assorted friends, spouses, partners, Coachman neighbors, and maybe–who knows–a half dozen off-shift Queen Soopers’ employees with nothing better to do.

The morning after my the party when Jim and I step out of the bedroom and out onto the battlefield to look over the wreckage, he tells me I had–not all at once, of course–eighty-one people stop by my birthday party.

Eighty-one.

Now let’s look in on an evening in February of this past year. It’s my 67th birthday. No surprise party. I’m celebrating not at home but at a restaurant, and not with eighty-one people but with three. And I’m feeling good. Not because I’m drunk–I gave that up in ’98–but because I’d recently broken my arm and I’m floating nicely on an och-see-COH-dun cloud. I know even without the narcotic I’d be feeling good, because I’m celebrating my birthday in the way I’ve come to enjoy celebrating birthdays lately–for that matter, all get-togethers: with a few good friends.

Remember I said in looking in the crawlspace of my memories I’d found not only my one big the party but also how that one the party has remained a baseline from which I’ve taken the measure of the last three decades of my life. You might guess that when I would look back over the years–at birthdays in particular–I would get a little upset to see the attendance shrink–from eighty-one in 1980 to three in 2012. I did the math: that’s a loss of 2.4375 persons per year. (I only had three friends at my last birthday party. If the average holds, I should look forward to only a partial person–a .5625 person–this year.)

It bothered me–once–this decline in attendance. Worse yet, back when I was drinking, I stupidly interpreted the numbers as a decline in popularity–and that didn’t just bother me, it depressed me. What I could possibly have done to scare away people, at the withering rate of 2.4375 persons per year?

The truth is in 1980 I was the victim of what I now call my stupidly busy days. Between my day-job selling bedpans and syringes, my night-job at the theater trying the best I could to be someone else, working in my off-hours to honor a grant I’d received to write a half dozen children’s plays, striving to be attentive to what was then a fairly new relationship with Jim, making sure I logged enough hours at the Foxhole and at this new place called Tracks, serving on the board of the alphabet-spare GLC, helping to put together a fundraising footrace for the then-fledging AIDS Project, and drinking way, way, way too much, my life at 35 was a runaway train. I was living the illusion of multi-tasking before anyone had even coined that fanciful term. I was having fun–but of course I was much, much, much younger.

I was having fun, but I was also going crazy. My stupidly busy days. Days, as I look back on them now, with a mirage of significance but without much lasting substance.

It’s now 2013 and I’m still busy, but looking in from the outside you’d never guess it. I call these days my wisely busy days. I’m out with two or three friends. Or I’m home. Out or home, I’m happy. My the party of 32 years ago, when I think about it, was not a slow descent into unpopularity, with unpopularity’s nasty side effect loneliness. Instead, my the party of 32 years ago was the beginning of what I like to think was my ascent to maturity, with maturity’s priceless bonus feature solitude–elective solitude. With maturity has come enough contentment sometimes to choose solitude and sometimes to be with friends. In yesterday’s stupidly busy days I was exhausted and my senses were blunted. In today’s wisely busy days I’m alert. It’s much better now.

And so there you have it: my the party. Today’s prompt has given me a chance to take a break from making up silliness and to stick close to what good storytelling can and maybe should do and that’s to share a little bit of the private me. Today’s prompt has given me a chance to tell you about my the party of long ago, an evening I continue to think of as the beginning of the best days of my life–my wisely busy days–and why, when yesterday afternoon I typed the first sentence–“Today’s prompt is the party; not a party”–I thought of my hero Thoreau and his saying:

It is not enough to be busy. So are the ants.

The question is: what are we busy about?

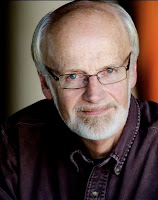

About the Author

Colin Dale couldn’t be happier to be involved again at the Center. Nearly three decades ago, Colin was both a volunteer and board member with the old Gay and Lesbian Community Center. Then and since he has been an actor and director in Colorado regional theatre. Old enough to report his many stage roles as “countless,” Colin lists among his favorite Sir Bonington in The Doctor’s Dilemma at Germinal Stage, George in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and Colonel Kincaid in The Oldest Living Graduate, both at RiverTree Theatre, Ralph Nickleby in The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby with Compass Theatre, and most recently, Grandfather in Ragtime at the Arvada Center. For the past 17 years, Colin worked as an actor and administrator with Boulder’s Colorado Shakespeare Festival. Largely retired from acting, Colin has shifted his creative energies to writing–plays, travel, and memoir.