Dying is easy, comedy is hard. This deathbed wisecrack has been attributed to a dozen different actors over the years; none of the attributions is provable. Nonetheless, the sentiment has something to say. Dying is unavoidable. But the living from which we harvest comedy—or humor—is sometimes very, very hard.

I’ve been coming to Storytellers for 11 weeks. I’ve not made every Monday get-together, when I have been here it seems I’ve delivered one bit of silliness after another. I’m pretty sure I’ve convinced you that’s my stock-in-trade. From a lottery winner trying to buy happiness to my queerness measured against the fury of a tropical storm to Hamlet sweating in his pumpkin pants, I’ve probably gotten you to expect every Monday more of the same. Of course, many of your stories have played the humor card, and I’ve loved them.

But I’ve sat here too most Mondays and listened to one or two stories that have not tried to be funny—stories that have pointed to times in the past when living was hard. These have been wonderful stories and I’ve been privileged to listen to them.

No doubt, there is great humor in this room. It’s high on the list of the many things that keep me coming back. When I’m not in this room, I find myself too much in a world in which there’s a lot of room for humor. All day long I see people going about with shoulders slumped, mouths downturned, eyes cast to the ground. They may be boundlessly happy inside—although something tells me they’re not. They go about as if they’ve forgotten what a great thing it was to have been born in the first place.

I come to this room, though, and find myself among people who don’t seem to have forgotten—people who are generally light-hearted, full of good-fellowship, people who are more likely to be merry than morose.

That said, I have a feeling there’s a history of a good deal of pain in this room. It may not be true for each of us, but, considering the number of years we’ve lived, the common denominator that brings us together—for that matter, the very nature of building we’re sitting in—there’s a good chance a number of us have negotiated some white water in our lives.

But it would be unfair of me to draw conclusions about humor and pain using your lives as a study group. The self-examined life is just that: an examination of self. The only fair study group is me—my experience of humor and pain.

First, though, a Surgeon General’s Warning: Confessions by a funny guy of lots of pain in his past are usually boring, filled with clichés, just begging for rejoinders such as “Yeah, tell me about it,” or “You think you’re the only one?”

But, so what? Here goes . . .

I survived my childhood; not too much scar tissue to show for it. I’ve given you peeks at my growing up, in a working class section of The Bronx, parents whom I now understand but whom I saw, when I was a kid, as cold and uninspired, a brother 14 years older and already out of the house, making me for all practical purposes an only child, a child scared of his own shadow but still longing for high adventure, your classic stay-in-his-room bookworm who felt safe only in his imagination, puzzled, perplexed, unsure from the start of everything from his gender, later his sexual orientation, and finally and overshadowing it all even his chances of ever being really happy.

In other words, a perfect hothouse for sprouting humor.

Robin Williams, on Inside the Actors’ Studio, when asked what in his childhood made him the man he grew into, answered—with a line that drew some unintended laughs: “I just had myself to play with.”

I laughed too when I heard Williams say that. But you know, when you think about it, having only yourself for a playmate—while it may be okay for some—for many of us—as it was for me—it meant lots of aloneness. In front of my parents, my grandparents, my aunts and uncles, I was the world’s happiest kid, the entertainer, the consummate clown. On holidays when relatives would come early and stay late, I’d maintain from morning until night, smiling throughout, growing more and more exhausted from having to pretend. And when finally the house would clear and I’d be excused from center stage, I’d go to my room, panting like I’d just run a race, and sit there listening to the sounds of The Bronx night: traffic going by on Crosby Avenue, late-night el trains squealing into Pelham Bay Station, planes flying unnervingly low on their approach to LaGuardia. I don’t remember crying on those nights in my room. I’m not crier. Never have been. I would just sit there, listening.

Thank God we grow up. Of course, for most people, childhood is the foundry that shapes the adults we become. I learned in the foundry of my own childhood that humor made a perfect shield for keeping people at bay, for helping me conceal my true feelings, for lending the appearance of truth to all the lies I would tell about how happy I was, and for providing me with the wherewithal to get through each day. My shield of humor gave me an illusion of normalcy, of maturity, of being an okay guy who had it all figured out. With my shield of humor in place, I could pass myself off as intelligent, intuitive, insightful, your best friend, your concerned co-worker, creative, industrious, a guy who was on top of things, unquestionably masculine, grounded in his sexuality—even if that meant occasionally pretending (I’m sorry to say) to be straight—all-in-all, a healthy, happy, jolly good fellow.

Relentless humor kept reality at bay. I used other techniques, too—alcohol chief among them. I don’t want to turn this into a story about my addiction—a “drunk-a-log,” as those who’ve been there, done that might call it—but for just a moment, it’s illuminating to know that, at least for me, humor and alcohol, for years, went hand-in-hand. The drunker I got, the funnier I got. Or so I thought. And if I’d start to bomb, lose my timing, I’d simply drink faster. If I ran out of jokes, I’d just drink. If the booze ran out, I’d go home.

Humor, comedy, joking around is—as Gene Wilder said—a drug; it gives you an endorphin buzz, and with time, you need more and more. It’s a passport, as Wilder said, back to a land you once spent a lot of time in as a child: the unknown. And the unknown, you learned as a child, is where you could feel safe.

It’s also the place where you could take risks you wouldn’t take otherwise.

But this isn’t a story about alcohol. It’s a story about humor. So one last mention of the booze . . .

When I quit drinking, 14 years ago, I found I was allowed to keep my sense of humor. In fact, when sober, much to my delight—and surprise—the humor, the comedy, the joking around got sharper, brighter, more incisive—less cruel, less trashy, less dumb. I found I didn’t need—out of my insecurity—to put down everyone and everything.

Humor, as someone said—when you first wield your protective shield—is creating an optional universe in which your insecure self can feel at home. As you become more and more comfortable with yourself, you can ease off the humor, take brave steps out of your optional universe, test the air in the real world. Sober, I was, for the first time in my life, comfortable—or reasonably so—in the real world. At the same time, I hadn’t been asked to surrender my passport to my optional universe, the unknown, the place I’d discovered as a child and where I was—and continue to feel—completely safe—safer still, if I’m to be honest, than in the real world.

So where does this leave me today? It leaves me a citizen of those two best worlds—the real one, in which I’m marginally comfortable, and the unknown, in which my humor continues to germinate.

But does saying that today I’m a happy citizen of those two best worlds, the real one and the unknown, mean I’ve got it licked? Hardly.

I live my life now to get back at it all. I live my life now in spite of the past. And I don’t mean that to sound vindictive or combative. Humor is my weapon of choice. I try not to use it against my parents. They tried. They’d been dealt a bum hand and they played it as best they could. I try not to use it against the uninspired environment I did my best to conform to but eventually had to escape. That was the way it was—the roulette wheel of birth. Millions of others were a lot worse off. I’m just happy to have been born in the first place. I try not to use it against the confusion I felt over identity and orientation; the lack of good role models and the guts to speak up. Those were primitive times compared to today. All these things were only parts—parts of a whole, a sum total. It’s the sum total I push back against today, every conscious minute—not with vindictiveness or regret; not even with avoidance. I do it with humor. Humor is my soft revenge.

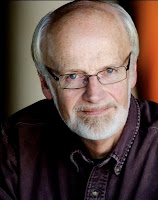

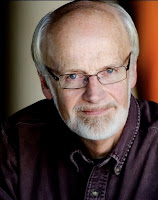

About the Author

Colin Dale couldn’t be happier to be involved again at the Center. Nearly three decades ago, Colin was both a volunteer and board member with the old Gay and Lesbian Community Center. Then and since he has been an actor and director in Colorado regional theatre. Old enough to report his many stage roles as “countless,” Colin lists among his favorite Sir Bonington in The Doctor’s Dilemma at Germinal Stage, George in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and Colonel Kincaid in The Oldest Living Graduate, both at RiverTree Theatre, Ralph Nickleby in The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby with Compass Theatre, and most recently, Grandfather in Ragtime at the Arvada Center. For the past 17 years, Colin worked as an actor and administrator with Boulder’s Colorado Shakespeare Festival. Largely retired from acting, Colin has shifted his creative energies to writing–plays, travel, and memoir.