In the summer of 1964, I turned

16. My father and I drove north to visit

my uncle. When we arrived, my aunt and

uncle were not home; dad went to visit with them while they were at a mutual

friend’s home elsewhere in the city.

This left my two cousins (ages 14 and 12) and me, home alone for several

hours.

16. My father and I drove north to visit

my uncle. When we arrived, my aunt and

uncle were not home; dad went to visit with them while they were at a mutual

friend’s home elsewhere in the city.

This left my two cousins (ages 14 and 12) and me, home alone for several

hours.

Being mischievous and mean spirited, my

older cousin decided to lock his brother out of the house. I actually helped him to do it, but he wanted

it to last for a while. In any case, the

younger cousin left to ride his bike to a friend’s house, so my conscience was

mostly clear.

older cousin decided to lock his brother out of the house. I actually helped him to do it, but he wanted

it to last for a while. In any case, the

younger cousin left to ride his bike to a friend’s house, so my conscience was

mostly clear.

At this point, my older cousin chose

to use the bathroom. After what seemed

like 10-minutes, or at least plenty of time to finish his business, I knocked

on the door and asked how much longer he would be in there. He said, “Not long.” I then suspected that he might be doing more

than what is customary in a bathroom; not an unreasonable supposition

considering that we had sex play each time I had visited before.

to use the bathroom. After what seemed

like 10-minutes, or at least plenty of time to finish his business, I knocked

on the door and asked how much longer he would be in there. He said, “Not long.” I then suspected that he might be doing more

than what is customary in a bathroom; not an unreasonable supposition

considering that we had sex play each time I had visited before.

I found the “junk drawer” in the

kitchen and found a small screwdriver and I inserted it into the bathroom

doorknob to “pop” the lock into the unlock position. It did so with a very loud “pop” sound. My cousin immediately shouted, “Don’t come in!” I rattled the knob, but did not go in. About a minute later he said, “Okay, you can

come in now.” Not knowing what to

expect, I entered.

kitchen and found a small screwdriver and I inserted it into the bathroom

doorknob to “pop” the lock into the unlock position. It did so with a very loud “pop” sound. My cousin immediately shouted, “Don’t come in!” I rattled the knob, but did not go in. About a minute later he said, “Okay, you can

come in now.” Not knowing what to

expect, I entered.

My cousin asked me if I wanted to play

as if we were the Gestapo torturing prisoners for information. I said okay and asked, “What are the

rules?” He explained that the prisoner

would stand in the bathtub with his hands holding the shower curtain rod and

could not let go; as if he were tied up.

The other person would pretend to torture the prisoner any way he wanted

as long as it was pretend and not painful.

He even volunteered to be the first prisoner. How could I say no? I began to play torture him, which did not

take too long evolving into sex play. We

eventually traded places, so I had my turn also as the prisoner.

as if we were the Gestapo torturing prisoners for information. I said okay and asked, “What are the

rules?” He explained that the prisoner

would stand in the bathtub with his hands holding the shower curtain rod and

could not let go; as if he were tied up.

The other person would pretend to torture the prisoner any way he wanted

as long as it was pretend and not painful.

He even volunteered to be the first prisoner. How could I say no? I began to play torture him, which did not

take too long evolving into sex play. We

eventually traded places, so I had my turn also as the prisoner.

As soon as we finished and exited the

bathroom, there was a knock on the door.

We thought it was the younger cousin returning home. It was not.

Instead, it was a 12-year old friend of my younger cousin. We let him in and introductions followed. He and I were chatting away about nothing

important while sitting at the kitchen table.

He asked me if I spoke Pig Latin.

bathroom, there was a knock on the door.

We thought it was the younger cousin returning home. It was not.

Instead, it was a 12-year old friend of my younger cousin. We let him in and introductions followed. He and I were chatting away about nothing

important while sitting at the kitchen table.

He asked me if I spoke Pig Latin.

When I was in elementary school, some

of us kids did dabble in it for a week or so, but it was not very interesting

to us so we dropped it; so I told him, “No.

I don’t speak it.” He promptly

turned to my cousin and said, “Owhay igbay isway ishay ickday?” My cousin held up his hands about 7-inches

apart. I then said, “No it’s not. It’s about this big,” holding up my hands to

indicate the size. The friend of my

cousin then said, “I thought you said you didn’t speak Pig Latin.” I told him that I don’t speak it, but I never

said I didn’t understand it.

of us kids did dabble in it for a week or so, but it was not very interesting

to us so we dropped it; so I told him, “No.

I don’t speak it.” He promptly

turned to my cousin and said, “Owhay igbay isway ishay ickday?” My cousin held up his hands about 7-inches

apart. I then said, “No it’s not. It’s about this big,” holding up my hands to

indicate the size. The friend of my

cousin then said, “I thought you said you didn’t speak Pig Latin.” I told him that I don’t speak it, but I never

said I didn’t understand it.

The boy wanted to see me naked right

then, but my cousin told him to wait until that night. As it turned out, that night my two cousins,

the boy, his 16-year old brother, and I had a sleepover in the family’s steam

bath outbuilding. There was a lot more

sex play, which started out by playing a game of Strip Go Fish.

then, but my cousin told him to wait until that night. As it turned out, that night my two cousins,

the boy, his 16-year old brother, and I had a sleepover in the family’s steam

bath outbuilding. There was a lot more

sex play, which started out by playing a game of Strip Go Fish.

Oh what a day, the night was even

better.

better.

© 24 Sep 2012

About the Author

I was born in June of

1948 in Los Angeles, living first in Lawndale and then in Redondo Beach. Just prior to turning 8 years old in 1956, I was

sent to live with my grandparents on their farm in Isanti County, Minnesota for

two years during which time my parents divorced.

1948 in Los Angeles, living first in Lawndale and then in Redondo Beach. Just prior to turning 8 years old in 1956, I was

sent to live with my grandparents on their farm in Isanti County, Minnesota for

two years during which time my parents divorced.

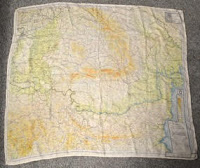

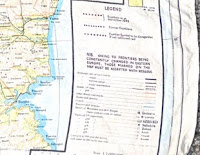

When united with my

mother and stepfather two years later in 1958, I lived first at Emerald Bay and

then at South Lake Tahoe, California, graduating from South Tahoe High School in

1966. After three tours of duty with the

Air Force, I moved to Denver, Colorado where I lived with my wife and four

children until her passing away from complications of breast cancer four days

after the 9-11-2001 terrorist attack.

mother and stepfather two years later in 1958, I lived first at Emerald Bay and

then at South Lake Tahoe, California, graduating from South Tahoe High School in

1966. After three tours of duty with the

Air Force, I moved to Denver, Colorado where I lived with my wife and four

children until her passing away from complications of breast cancer four days

after the 9-11-2001 terrorist attack.