I was helped out of the closet by a man who died in 1935—ten years before I was born—a man who never successfully got out of his own closet. In other words, this man who helped me out of the closet lived and died a closet case.

I’m going to begin, though, in telling you how, in 1959, I became acquainted not with the man who helped me out of the closet but with his surviving brother, under totally unrelated circumstances—

It’s 1959. I am 14 years old. I’m living with my mother, father, and older brother in a second floor walk-up apartment in the East Bronx. I know you’ve heard me talk about my growing-up years in The Bronx a number of times before. It helps though to visualize my working-class surroundings in order to understand the improbability of a kid in the East Bronx making the acquaintance of an Oxford professor of archaeology. In my growing up years, fathers, like my father, were laborers. Mothers, like my mother, were housewives. Fathers disappeared each morning to their factory jobs on the elevated subway—the “el.” Mothers led kids like me to public school. They shopped. And they cooked. I say with complete kindness my father and mother were not very well educated. They had come through the Great Depression, and in all things did the very best they could.

I had an uncle though, a lion of a man, who, as a highly educated man, was an outlier in the family. He recognized in me a kindred bookworm. One day he delivered—to an apartment that could barely accommodate it—a 33-year-old set of the Britannica. The 1926 Britannica.

Fourteen-year-old me wanted to be an archaeologist. I read in the Britannica every article I could find on archaeology. One article on Persian archaeology especially excited me. I decided to send the writer what today we would call a fan letter. The writer, the Britannica told me, was a “Arnold W. Lawrence, professor, Oxford.”

I wrote my fan letter. In my innocence, I had addressed it to “Professor Arnold W. Lawrence, Oxford, England,” not knowing Oxford was a conglomerate of universities, and forgetting that the man who had written the article had written it more than three decades earlier.

But months later I received a reply, from A.W. Lawrence, London. Professor Lawrence, 60, retired, was apparently stunned to get my fan letter. In 1926 for A.W. Lawrence, the Britannica article was an extraordinary credit. Professor Lawrence’s reply to my fan letter–a tissue-paper blue aerogram (which I have safely at home) was the beginning of a correspondence that lasted up and down, on and off for 31 years—although (and this is another story for another Monday), I met Professor Lawrence face-to-face only once, in 1990, two months before his death.

Now, though, to bring the two brothers together—

We move forward, from 1959 to 1962. I’m 17, studying architecture (so much for archaeology) at a vocational art school in Manhattan, and I’m corresponding every month or so from our second floor walk-up with this retired Oxford professor in London. And, I’m still closeted. A movie opens in Times Square, David Lean’s epic Lawrence of Arabia. I go to see it. I’m blown away. I never make the connection though—Lawrence and Lawrence—why should I? Lawrence is not an uncommon name. I want to learn more about Lawrence of Arabia. I stop in a midtown bookstore and I find a ratted copy of the Penguin The Essential T.E. Lawrence (that’s Lawrence of Arabia: Thomas Edward Lawrence). On the subway to the Bronx I pop the book and read in the sketch biography: “Thomas Edward Lawrence . . . five brothers . . . the youngest, Arnold Walter Lawrence.” Could this be? I think, this man I’ve been corresponding with for three years, could he be Lawrence of Arabia’s youngest brother? I write and ask, and of course he is.

Thomas Edward Lawrence was born in 1888. His story is generally known, thanks to David Lean’s movie. Briefly: Lawrence studied at Oxford to be an archaeologist, went on a British Museum sponsored dig to the Middle East; at the onset of the First World War, he was drawn into British Army intelligence. Lawrence locked in his legacy during the war as guerilla mastermind of the Arab Revolt. At the war’s end, now Colonel Lawrence returned to England, sought to influence the Paris peace talks on behalf of the Arabs–failing that, and deeply disillusioned, he spent his remaining years running from the spotlight. Finally, four months before his death, Lawrence retired to a small cottage in Southern England, to wonder, as many of us to at such junctures, What next?

But here I am in 1962, and for me Thomas Edward Lawrence is a movie. Not expecting the life affirming discovery I would make, I read everything I can find of T.E. Lawrence’s, chief being his massive, magnificent war memoir Seven Pillars of Wisdom; also, his thousands upon thousands of letters—letters to such notables as Winston Churchill, Edward Elgar, E.M. Forster, Robert Graves, Ezra Pound, and George Bernard Shaw. My discovery, sometimes on the surface of Lawrence’s writing but more often between the lines, was that this man Lawrence—Lawrence of Arabia, warrior, author, scholar–was a deeply conflicted man, almost certainly over his sexuality, and possibly, if you comb carefully enough, over questions of gender. I sat in my bedroom in The Bronx reading this stuff and thought, Holy shit, this is me!

At that time I was at a point familiar to many of us—sensing a difference in me, fearing that difference made me a lesser person, somehow sure I couldn’t talk to others about my difference, and resigned to living a life of reduced accomplishment because of this difference. But here was Lawrence of Arabia . . .

Was Lawrence homosexual? (I’ll use “homosexual.” It seems more fitting for an Edwardian man.) No one knows for sure. In certain of his letters, Lawrence denied any sexual experience. Yet he was certainly (what we would call today) gay-friendly. Among his closest friends were men like E.M. Forster. Cited often is a suspicious friendship with a teenage Arab boy when Lawrence was a twenty-something archaeologist. The boy, Selim Ahmed—initials S.A.—is possibly the person to whom Lawrence dedicated Seven Pillars of Wisdom, with its introductory poem, S.A., which opens: I loved you, so I drew these tides of men into my hands/and wrote my will across the sky in stars. In Seven Pillars Lawrence, seeing the intimacy enjoyed by some of his young fighters, tells us here is “the openness and honesty of perfect love.” In another chapter he describes “friends quivering together in the yielding sand with intimate hot limbs in supreme embrace.” (There were few such “intimate hot limbs in supreme embrace” in David Lean’s movie.) Then, too, in a letter to George Bernard Shaw’s wife, Lawrence wrote “I’ve seen lots of man-and-man loves: very lovely and fortunate some of them were.”

Can you imagine what effect this sort of thing had on closeted me? No one—me included—can say with certainty that T.E. Lawrence was homosexual. But for me, reading his man’s books and letters in my Bronx bedroom all those many years ago, T.E. Lawrence was homosexual enough, enough for me to open my own closet door. My God, I thought, here’s a man troubled as I’m troubled, and he’s written his will across the sky in stars!

I will regret, though, Lawrence himself never got out of his own closet. This, for me, remains a note of sustained sadness. Having retreated to his cottage—alone—Lawrence wrote to a friend—and I have often felt this to be one of the most melancholy snapshots of a life not fully realized—Lawrence wrote: “I’m sitting in my cottage rather puzzled to find out what has happened to me. At present the feeling is mere bewilderment. I imagine leaves must feel like this after they have fallen yet alive from their tree, now on the ground, looking up, and until they die, wondering.”

A week later Lawrence, in a motorcycle crash, suffered fatal head injuries. He died six days later, never having recovered consciousness. He was 46. Lawrence was buried in a country cemetery not far from his cottage. A.W. Lawrence, his youngest brother, my correspondent, was the senior pallbearer.

_______

Fifty-six years later, in February of 1990, I meet A.W. Lawrence face-to-face for the first time. The meeting was arranged by a mutual acquaintance. I am at Lawrence’s bedside. He’s 90 years of age. We reminisce about our lifetime correspondence. I show A.W. the aerogram he sent in 1959. He reads it very, very slowly, and at the end says, “Well, quite a good letter, that.”

I leave with a promise to return in the summer. But I return home one day in April to my Capitol Hill apartment to find on my answering machine a message from our mutual acquaintance: “We’ve lost our dear friend, Ray. A.W. passed quietly last Sunday. That’s it then, Ray, isn’t it, the end of an era.”

I telephoned the acquaintance to hear him say that my friendship with A.W. Lawrence—a friendship that was founded on A.W. himself and not on his famous brother—my friendship, particularly in his last years, had given back to A.W. his own identity.

______

Although I consider myself successfully un-closeted, there does remain a pocket of silence, one that will always be there—

What I was never able to say to A.W. Lawrence in 31 years was how grateful I was to his older brother—how this older brother, T.E. Lawrence, who had written his name “across the sky in stars” but who seems never to have made peace with his identity—how this older brother had managed to give a boy in the Bronx the gift of his own identity.

______

A footnote in closing:

If Lawrence of Arabia helped me out of the closet, and I considered myself fully out (the exception being the one pocket of silence I just mentioned), why then have I contributed my stories to our website under the name Colin Dale? Why not under my own name? Believe me, this is not another pocket of silence. Twenty-some years ago I and a friend were riding the London underground. We got off at a station stop called Colindale. Colindale: one word, no space. My friend said, “That’s not too shabby a name, Colindale. It would make a good alter-ego.” And so ever since if I write something that I send to my friend, I write it as Colin Dale: two words.

If you were to look at a map of the London underground, you’d see that if my friend and I had gotten off one stop sooner, today I’d be Hendon Central. One stop later, I’d be Burnt Oak.

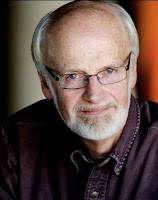

About the Author

Colin Dale couldn’t be happier to be involved again at the Center. Nearly three decades ago, Colin was both a volunteer and board member with the old Gay and Lesbian Community Center. Then and since he has been an actor and director in Colorado regional theatre. Old enough to report his many stage roles as “countless,” Colin lists among his favorite Sir Bonington in The Doctor’s Dilemma at Germinal Stage, George in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and Colonel Kincaid in The Oldest Living Graduate, both at RiverTree Theatre, Ralph Nickleby in The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby with Compass Theatre, and most recently, Grandfather in Ragtime at the Arvada Center. For the past 17 years, Colin worked as an actor and administrator with Boulder’s Colorado Shakespeare Festival. Largely retired from acting, Colin has shifted his creative energies to writing–plays, travel, and memoir.